New Approach to Self Determination

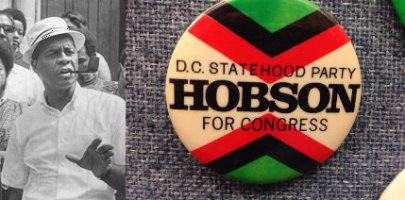

Julius Hobson, founder of the DC Statehood Party

“Statehood is a clear, just, and attainable goal to which District residents can aspire,” declared publisher Sam Smith, in the June 1970 issue of the DC Gazette, an alternative newsweekly. “That’s what we should demand, not some more benevolent form of colonialism foisted off as ‘home rule’… Our right is entire membership in the United States of America as the 51st state.” Today, this statement would seem more than reasonable to a majority of Washingtonians and a growing number of people from the 50 states. Considering 220 years of being denied a voice in our national government and the harm and humiliation visited on DC by Congressional interference, most DC residents would find it obvious.1

Yet in the summer of 1970, the response to Sam Smith’s “Case for Statehood”” was, as he recalls, “underwhelming.” Most Washingtonians concerned about self-determination were focused on incremental steps. They were enthusiastic about pending Congressional legislation that would grant the city a non-voting delegate in the House of Representatives, and they were hopeful that the House would finally approve a home rule bill that had been passed many times by the Senate.2

While many DC residents were eager for the DC home rule legislation to advance, Sam Smith was one of the few Washingtonians who recognized the shortcomings of what he dubbed “colonial reorganization” and Julius Hobson called “home fool.” Their successful battle against the efforts of powerful Congressmen to slice the city with freeways, made the limitations of home rule very clear to Hobson, Sammie Abbott and their allies. They were well aware that the authority the U.S. Constitution gives Congress over the District of Columbia could be used to overturn the actions of a home rule government and thwart the will of DC citizens.3

In the fall of 1970, after Congress passed the DC delegate legislation, a special election was set for March 1971. To Hobson and anti-freeway activists Sammie Abbott and the Reverend Joe Gipson, this election offered an opportunity to advocate for statehood. They formed the D.C. Statehood Committee with the immediate goal of adding a statehood referendum to the Delegate election ballot. DC election officials informed the Committee that while it would take a court order or Congressional action to put the proposed referendum on the special election ballot, the Statehood Party itself could appear on the ballot with a Delegate candidate who had gathered several thousand signatures.4

Advocacy for DC statehood then became Julius Hobson’s campaign for Delegate. When Sam Smith, Julius Hobson, Lou Aronica and others met to plan the campaign, Smith’s “Case for Statehood” became the platform and the rationale for the new DC Statehood Party. Julius Hobson became co-chair, as did Josephine Butler, who took on organizational and administrative responsibilities. Hobson’s supporters proudly offered DC voters what they considered a much better way to achieve self-determination than the incremental approach championed by Walter Fauntroy, the Democratic candidate. After Fauntroy handily won the election, the new DC Statehood Party turned its attention to Congress.

In the spring of 1971, Lou Aronica went to work on drafting statehood legislation. “I took a crash course on how other places became states,” he recalls. “And I relied heavily on Alaska and Hawaii.” In the summer, two statehood bills were introduced in the House of Representatives. The first, by Republican Fred Schwengel of Iowa, proposed that the entire District of Columbia become a state. The second, introduced by California Democrat Ron Dellums was based on the platform of the DC Statehood Party. It called for the residential and commercial areas of the District to be the 51st State. Dellums’ bill closely resembles the legislation that was passed by the House of Representatives on June 26. However, in 1971, the statehood legislation went nowhere, largely because of the opposition of Delegate Fauntroy, who also successfully blocked its introduction in the Senate.5

1 https://samsmitharchives.wordpress.com/1970/05/03/dc-statehood-the-first-article-advocating-it/; Sam Smith, “The Case for Statehood,” D.C. Gazette (June 1970).

2 Sam Smith, Captive Capital: Colonial Life in Modern Washington (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1974), 271.

3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrPBc6J27fk&list=PLe1dVYayEM7qpQRU6iPRXXkylV4zCCOWq&index=37&t=0s; Lou Aronica, oral history interview by John Hanrahan, April 25, 2014, interview 36 in Washington DC Lessons of the Sixties-wix.com series; “Statehood is Far More Difficult,” Washington History, Fall 2017.

4 “House Unit Votes for D.C. Delegate: Nonvoting Member,” Washington Post, July 30, 1970; “Group Opens Drive for D.C. Statehood,” Washington Post, Nov, 26, 1970.

5 Smith, Captive Capital. 271; Debby Hanrahan. DC Statehood Party leader, phone interview with Elinor Hart, April 6, 2020; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nrPBc6J27fk&list=PLe1dVYayEM7qpQRU6iPRXXkylV4zCCOWq&index=37&t=0s; Lou Aronica, oral history interview by John Hanrahan, April 25, 2014; “D.C. Statehood Bill Introduced,” Washington Post, June 18, 1971; “Statehood Is Proposed in Second Bill,” Evening Star, July 7, 1971; “Fauntroy Attacks Plan on Statehood,” Washington Post, July 15,1971.

Where to Find Us:

New Columbia Vision

1651 HOBART ST NW

Washington, DC 20009

Phone: 202 387-2966

What's New

Extended business hours

To accomodate our customers' busy schedules, we have extended our hours and are now open later.

Special Facebook Promotion!

Like us on Facebook and get 10% off your next order.